|

This story was published in Radio Recall, the journal of the Metropolitan Washington Old-Time Radio Club, published six times per year.

Click here to return to the index of selected articles.

|

|

THE SINGER EARNS HER STRIPES: The Jane Froman Story

by Cort Vitty © 2006

(From Radio Recall, December 2006)

Author's Note: During World War II, entertainers in general and specifically radio stars, were a patriotic lot, supporting the war effort by building morale through bond drives and camp shows. Standing out among this well intentioned group of performers was singer Jane Froman, who without question was an American hero through her contributions to the effort. The stories of her courageous exploits follow; they gained worldwide attention during the war and clearly should never be forgotten.

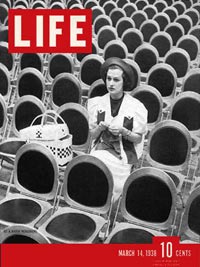

A solitary figure is curiously seated alone among a sea of empty chairs. It’s a dark haired young lady, in a candid picture on the cover of popular Life magazine. The publication is dated March 14, 1938. The grainy black and white photo is framed in the distinctive red border and merely identified as “a radio rehearsal.” On the inside pages a blurb names the attractive woman as Jane Froman; she’s knitting, while patiently awaiting her turn to rehearse in NBC’s mammoth studio 8-H. A solitary figure is curiously seated alone among a sea of empty chairs. It’s a dark haired young lady, in a candid picture on the cover of popular Life magazine. The publication is dated March 14, 1938. The grainy black and white photo is framed in the distinctive red border and merely identified as “a radio rehearsal.” On the inside pages a blurb names the attractive woman as Jane Froman; she’s knitting, while patiently awaiting her turn to rehearse in NBC’s mammoth studio 8-H.

In many ways, the cover depiction is analogous with Jane’s life story: Although a star in the medium of radio, she was no stranger to feeling isolated and alone. At the time, she had no way of knowing her greatest challenge would lie ahead: as the survivor a horrific plane crash while serving our country during World War II.

Ellen Jane Froman was born on November 10, 1907 in a suburb of St. Louis Missouri. During the first five years of her life, everything seemed just fine within the Froman household. The serene atmosphere was suddenly jolted by the mysterious disappearance of her beloved father, Elmer, whom she absolutely adored. The exact circumstances of the family breakup were never fully learned by Jane, although unfounded sightings of her dad in faraway locations would persist for many years. It was during this uncertain time that young Jane began to stutter; an affliction that would persist in varying degrees throughout the rest of her life.

The family breakup left Jane’s mother Anna in the unenviable position of having to make ends meet as a single parent. Various jobs did not produce enough income, resulting in a move to the home of Jane’s maternal grandmother in Columbia Missouri. In those surroundings, she discovered the indomitable spirit of the female members of her family, making quite an impression on her as a young child.

In a new town and attending a new school, Jane felt ostracized by the other children who taunted her for living in a single parent home. The isolation was painful, but made her defiant and all the more determined to succeed.

Mother Anna was musically adept and sought to cultivate her daughter’s talent, which developed through secondary education at Christian College and later at the University of Missouri. Talented Jane unquestionably became the star of many campus productions and started receiving accolades for her prowess as a singer. Sent to study music at the Cincinnati Conservatory in 1928, she happened upon a party where she met Powell Crosley, the owner of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team. Crosley, who also owned station WLW, heard Jane sing at the party. He liked her contralto voice and asked if she’d consider performing on the radio.

Jane accepted and for the next 2 years she worked tirelessly at WLW, doing mostly an assortment of commercials, during all hours of the day and night. Eventually, she progressed into doing two 15 minute shows a week. It was a 2:00 a.m. broadcast that brought her to the attention of listener Paul Whiteman, who was traveling through Cincinnati with his entourage of musicians, en route back to Chicago.

Another performer on station WLW was announcer Don Ross, who met Jane for the first time as she segued into radio. Initially, they became good friends while making frank and accurate recommendations regarding the career moves of one another. Don reportedly taught newcomer Jane proper microphone technique and other early tricks of the trade.

Ross moved to Chicago in 1931, promising Jane he’d watch for opportunities in the windy city. Upon hearing various female singers on Chicago radio, Don encouraged Jane to head for Illinois, albeit without a job. Soon after arriving, she landed a spot on the Whiteman program; then feisty Jane used her determination to arrange an audition at NBC, getting a job singing on Florsheim Follies. Don and Jane eventually wed and were even termed “Radio’s Happiest Couple” in a 1934 issue of Radio Guide magazine.

New York beckoned and Jane’s singing career really took off in the big city. She debuted on the Chesterfield Hour, starring Bing Crosby in 1933, as her popularity rose among listeners. Next, offers from Broadway began to pour in; she was even asked to join the famed Ziegfield Follies for a one year engagement.

In 1934, Jane was appearing regularly on many top radio shows. The ubiquitous radio polls of the day even voted her the year’s top female singer. Despite her stuttering, Jane was able to sing flawlessly. If a show called for speaking role, another actress would be called upon to deliver her lines. At one time, Arlene Francis handled such an assignment for Jane on the Stage Door Canteen program. One evening an unnamed actress, ready to deliver words on Jane’s behalf dropped her script at the last second; gutsy Jane stepped to the microphone and delivered the lines flawlessly. Jane’s stutter was no secret among co-workers and audiences of the day; she stuttered when casually speaking with friends and didn’t care who knew about it.

A short film career ensued, as Jane went to Hollywood and appeared in a handful of less than memorable pictures in the mid 1930’s. Although photogenic in front of the camera, Jane’s stutter hindered the delivery of lines and she was soon relegated back to the ether land.

Famed composer George Gershwin asked Jane to introduce a new ballad penned for the stage play Porgy and Bess. The song was titled Summertime and although it’s been recorded by dozens of artists, Gershwin thought the Froman version to be the most touching rendition, performed with a deep and genuine feeling in her voice.

Although the 1938 Life Magazine cover may have been a feather in her popular cap, all was not well in Jane’s personal life. Her marriage to Don Ross was on the rocks; just as her career soared, his soured. She took time off to help his professional life, but it didn’t improve. On the national front, 1938 was a year that saw the world situation teeter toward the possibility of war; trouble was brewing throughout Europe and a worldwide crisis was definitely in the making.

Jane was one of the first performers to realize our men and women in the armed services may soon be summoned. She began donating her time to entertain troops at military bases and camp shows in 1940. After Pearl Harbor in 1941, Jane pretty much heard the call to action and was a regular on the bond drive scene. The US Army recognized her commitment to service and made her an honorary sergeant; she earned her stripes through hard work and a commitment to the war effort.

In an interesting related story, Jane was home in Missouri, doing a benefit, when she noticed the assembled crowd at her concert was made up solely of a white audience. Dismayed to learn the reason was segregation, Jane insisted on performing the show across town for members of the African American community. Jane understood from an early age what it felt like to be left out and would not accept any form of discrimination.

In December of 1942, a little less than a year after Pearl Harbor, entertainers were recruited to begin going overseas as a morale boost for our troops. Naturally, Jane was one of the first to be approached and agree to go; she even volunteered to lead a troupe of entertainers. Based on the news of her imminent departure, Jane kept a packed bag with her at all times -- ready to go on a moment's notice.

Word finally came down on February 20,1943, with accompanying orders to depart the next day from New York’s Municipal Field at LaGuardia airport. Passengers boarded a Pan American 314, the legendary Yankee Clipper, in service as part of the fleet since 1939; the 39 people on board included flight crew, military personnel, correspondents and entertainers. The planned route would ultimately take them to London, with a stop at Lisbon Portugal.

On the evening of February 22, the ill-fated trip abruptly ended when the plane came to a screaming crash into the murky bacteria laden waters of the Tagus River, near Lisbon. Jane was severely injured, suffering a compound fracture above her right ankle that almost severed her leg; a deep cut below her left knee; multiple breaks in her right arm; assorted sprains, broken ribs, bruises and cuts. Jane bobbed around in the water, helplessly unable to swim; her cries were heeded by crew member John Burn, who helped her stay afloat.

For almost an hour, the injured clutched random pieces of wreckage while help was on the way. Of the 39 people on board, only 15 survived the impact. Everyone seated around Jane perished in the crash. She’d be haunted for the rest of her life over trading seats with singer Tamara Drasin Swann just before the plane went down; Tamara did not survive the wreck. When finally rescued from the icy waters, Jane recalled gripping her right leg for fear it may fall off.

The survivors were rescued by a Portuguese fishing boat and ushered to a Lisbon hospital, where staff was clearly not prepared for such massive injuries to so many people. Jane essentially had to wait for emergency medical help until the next morning, when surgery took place. Doctors wanted to remove her seriously injured right leg, but the determined singer somehow convinced the attending physician not to take her limb. Later she recalled the desperate feelings of isolation she felt as she lay broken in body and spirit; injured in a strange land with literally nothing left but a small cross she wore. She would question her own will to live, yet still fought to stay alive.

The cause of the crash was never fully determined. Port officials reported storm clouds over the river, with a little rain, accompanied by lightning. Radio contact from the aircraft indicated all was well aboard. The runway was in sight of the plane when the last words from the airship were received, indicating a plan to bank right in preparation to land. It was surmised a low air pocket may have caused a wing to touch the water. The Clipper previously had crossed the Atlantic over 240 times, flying more than 1,000,000 miles during its history.

For two months, Jane was literally wrapped in a cast from shoulder to toe. When well enough to travel, she declined a return trip to the states via plane and instead boarded a freighter. Once back in the USA she had her first of the 39 surgeries she’d endure throughout her life. At the time, a new drug called penicillin had been introduced and President Roosevelt stepped in to order heavy doses of the antibiotic on Jane’s behalf.

In October 1943, only eight short months after the ordeal, the Froman determination got her back into the public spotlight when she starred in Artists and Models. The play was met with much adoration by a truly appreciative public admiring her gutsy comeback. Jane looked radiant in her role; however she physically had to be carried on stage to perform. Her deformed and scarred legs were discretely hidden by a long gown; sleeves covered her badly scarred right arm. As surgeries continued, she would graduate to a wheelchair and finally the use of canes to move about. She would learn to carefully walk again mostly through her own determination.

Miraculously, by 1945 she again heeded the call and went overseas to entertain hospitalized troops. Jane performed while on crutches to appreciative audiences of injured servicemen. The fact that she too was injured in the line of duty became an inspiration to the wounded. Her courage lifted the spirits of the men in uniform, many of whom decided if she could do it, they could too. Jane performed thirty five shows in Germany, France, England, Austria and Czechoslovakia, covering over 30,000 miles in 3 months of touring.

All of the medical procedures and rehab eventually led to her dependence on pain killers. During the period after her accident, up until 1949, she realized she had a problem and personally did something about it by literally taking herself off medication. The turmoil of her post war recovery continued; paradoxically, as her physical problems mounted, her stutter began to disappear. After years of marital difficulties, Jane divorced Don Ross in February of 1948. She later, she married John Burn, the crew member on the crashed clipper who helped save her life; they divorced in 1956.

Hollywood made a film about her crash and rescue titled With a Song in my Heart, starring Susan Hayward; Jane performed her own songs and served as technical advisor on the 1952 film. The picture was a hit and revitalized her career, resulting in more radio, club and television work. Renewed interest in her courageous story brought financial rewards, which helped pay her huge backlog of medical bills. Jane had her own TV show, from 1952 until 1955.

She retired in 1961 and essentially only performed in local benefits for charity. Jane married for a third time in 1962 when she and old college chum Rowland Smith tied the knot. Retirement for Jane was unfortunately not entirely a happy time. Although selflessly active in the community and always there to help others, her physical problems advanced with age. Jane deteriorated seriously after a car accident in 1979, which further aggravated her old injuries. She passed away of a heart attack on April 22, 1980 and was buried at Columbia Cemetery with the small gold cross that survived the 1943 crash.

How good a singer was she? In the 1930s, impresario Billy Rose was once asked “who were the ten greatest singers?” He replied, “Jane Froman and nine others.” Jane is one on the few celebrities with 3 stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: one for radio; a second for TV and a third for her Capitol Record recordings.

Source Material: 1) DeLong, Thomas, The Mighty Music Box. Amber Crest Books Los Angeles Ca: 1980 2) Stone, Ilene, Jane Froman : Missouri’s First Lady of Song. University of MO Press: 2003, plus Articles in 3) Radio Guide, 4) Chicago Tribune, 5) Los Angeles Times, 6) New York Times, and 7) Washington Post

|